If you really want to get over a trauma you have to deal especially with the painful parts and even more difficult is to accept and admit own failures and unpopular reasons or relations. To ask questions and open a discussion about it is a start and can be done in many different ways. As well with a kind of informative and artistic help to sociocultural psychotherapy. The photographer and historian Dana Arieli from Israel captures the relics of the past and highlights the different aspects of dealing or not-dealing with its remains. As a history professor she is continuously introducing ancient times and gone moments to the present.

Dana visited hundreds of places where tragedies happened, but as well cultural sights and unknown ruins. Especially the ones not popular or not open for public need more attention. In 1984 it all started with a visit at the Concentration Camp Dachau in Germany with her first photographs. Heaps of other places and countries should follow during her searching and collecting travels, just in Germany she has been 35 times. The artist´s extensive gallery is open and accessible on the internet with a map and sorted by different topics.

Dana´s Phantom Photography Project went online in 2018 with a huge assortment of images from all the places she visited categorized in areas like “Nazi Phantom”, “Anschluss Relics”, “Atlantic Wall”, “Soviet Phantom”, “Fascist Phantom”, “Polish Phantom”, “Greek Phantom”, “KZ” or “East Asia”. The concept of the website is to choose an image which touches you and write a comment below it. Meanwhile there are already over 1000 comments on the platform from people from all over the world.

For the group exhibition “Echos” Dana Arieli was invited with her artworks to the art gallery “Kunstverein Montez” by the artists Julia Roppel and Rainer Raczinski. On the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the partnership between the cities of Frankfurt and Tel Aviv ten artists showed their works – five from Germany and five from Israel. There I met Dana and of course I was excited about her doings and the Phantom Map with the tagged photos reminded me a lot of the maps I am providing here on the website. So we recorded an interview about her art and the project. You can listen to the podcast or read the written down conversation filled with photos from Dana.

Here at this exhibition you are mainly showing photographs from Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan and the remaining architecture and survived trees from the atomic bomb.

The title of this project is “Hypocenter”. Because hypocenter is basically the place where the atomic bombs, Little Boy and Fat Man were dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki within a difference of three days back in 1945. So this was on August 6th and on August 9th. The result of this very traumatic event is at least a quarter of a million people passed away. Either in the immediate day or in the period which followed. And my visit took me back to those two cities in 2017 and in 2019 in order to figure out what can I find after so many years have passed. During my first visit to Hiroshima in 2017 I was encountered with a very interesting concept. And the concept was “A-Bombed Trees”. And when I was asking: “What am I looking at?” I was told in Japanese: “We have a concept for a person who survived the atomic bombs, which is called Hibakusha. But we also have a concept for a tree that survived the atomic bombs.” This was for me really fascinating, so I decided to try to visit all the trees that were very close to the hypocenter. Most of the ruins in basically a radius of about 500 to 2000 meters survived.

There is a whole culture that got traumatized and you tried to capture parts of their healing process and how they are dealing with it. They are treating trees like with medicine and they are putting bandages around it. The photos show not only the remains, they show as well part of the endurance the whole country is still going through.

Absolutely. First of all we must understand that back in 1945 most of the trees and most of the houses were completely vanished. Because they were using wood to build the houses. And when the atomic bombs were dropped, everything was burned. So why do we have some surviving trees? Because the Japanese concept was that very important buildings like primary schools or hospitals or even in some cases entries to shrines were built with stone and concrete. So at these places there were sometimes trees and awkwardly enough of those trees survived the atomic bombs. Now because trees are so sacred for the Japanese society, in their concept and their thoughts, they started to treat them immediately after 1945 and of course it wasn´t open to the West. Even today when you visit Nagasaki you don´t get information for the English, German or Italian speaker. The information, if it exists at all, is only in Japanese. In Hiroshima two years ago they decided to have a tourist guide who takes you around to some of those survived trees. But this is completely new. Their mentality to look at trees is as if it´s a really sacred alive thing that needs to be kept. And therefore, yes, you are right. They are still treating them. They want to find solutions in order to promise that everything needs to be done to keep those trees alive. And when I was in Hiroshima I actually came across a tree that died in 2016 and I was told that in the process of its burial there was sort of a funeral and even the prime minister came to visit. And they are still taking the seeds out of these trees and sending them around the world as a message of peace.

That really shows how high the value of those trees is for their culture.

Exactly. But if I want to be a bit critical of what I´ve seen. Of course the aesthetics is amazing. This is a society that has been driven through the aesthetics and especially the one of plants. But the mentality if you think about it in terms of dealing with it like for instance in Germany . If I make a comparison and if I look at Berlin or Munich, cities in Germany they are really commemorating their past. So of course there is also a critical aspect regarding what happened here in the 40s. We are mentioning now 75 years of the elaboration of Ausschwitz and German society knows how to take responsibility. If you look at Japan, they see themselves as victims. So there is still not any true dialogue to the questions “Why did it happen?” or “Was Japan only a victim or was it also a prosecutor?” There is no discussion of the responsibility and also there is an extreme gap that needs to be closed. It´s really interesting the way how they are looking at it, but it´s very different from what you see over Europe. Now for me this project is not just about documenting the relics, it´s also about introducing history to the present. So letting people participate as my viewers for instance in these exhibitions. Like in Frankfurt.

Yes, it´s everywhere important.

Yes, I agree with you, this is really important and therefore I have established a website. I think the reason why I started it was in order to ask people to come in, to choose an image, like the images we have seen before, and then drop a few words in a comment. In German, in Japanese, in Arabic, in Hebrew. I have already some reactions in Japanese and it´s going to be very interesting to see in the future while I exhibit it to maybe open up a discussion. Or a channel for discussion that wasn´t open before. So the name of the website is www.phantoms.photography.

Actually it is some kind of an artistic way to help with sociocultural psychotherapy.

I think so. I think an image can cause you and make you look at things from a different perspective. The reactions that I get from some of the viewers is like this: “I would never have dealt with that topic unless I saw something that intrigued me and I wanted to keep on searching and then I realized your topic, and ok, now I am sitting here down to write. But these are kind of topics I don´t want to deal with, because it belongs to ancient history.” I don´t think it belongs to ancient history.

No, of course not. But these topics are painful and nobody want to deal with painful things. But if you really want to get over stuff you have to deal with the painful part as well.

Yes, that´s right. Let me tell you something about some German artist. There is one I really admire and I really like to quote. He was born with the name Herzfelde, but then he changes his name to Heartfield. His name is John Heartfield. And he passed away back in the 60s. I think it was one of the most brilliant political artists active in the 20th century. And he was talking all the time about the fact that art has an obligation. It has a commitment towards society. The way you can do it, it doesn´t have to be necessarily a political poster.

It can be mentally or emotionally, it doesn´t have to be political. But if you know you can have effects, you have to do it. If you see and if you realize what´s going on and you are able to do something, even if it´s a little poking, you have to do that.

Exactly. And that´s why I always quote Heartfield and he was writing about the commitment of the artist. I think also he had a lot of ethics. This was a guy with a world view. And I admire him. Many of the works that I do are sort of gestures to other artists. This is one of the artists I really want to do a gesture to as well.

How did you start with your art? When did you start taking photos and how did your passion and creativity develop?

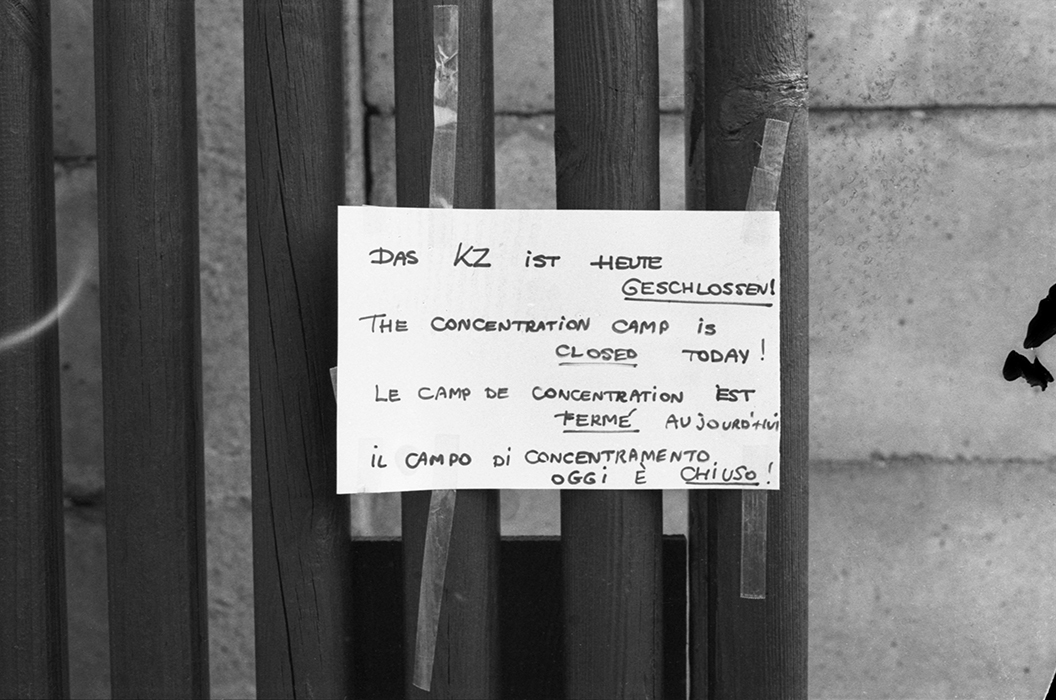

Well, probably the first photo I took was when I was six years old. Now I am 56 years old, but we don´t want to go through the last 50 years. So we do it very shortly. It took me many years to come back to photography. My first images were taken in the 80s. Actually my first image was taken here in Germany. I was visiting back in 1984 Dachau and I was really anticipating this visit. It was a very difficult time and at that point hardly any people visited from Israel. Today it is a different story. But it was back in the 80s then. And I wasn´t ready to the sign that I found there. There was a sign in four languages and the first line was in German, but I couldn´t read German by then. The sign was saying in four languages “The concentration camp is closed today”. And there was a line under the word closed. So this irony back in 1984 was something I wasn´t ready for. I was really waiting for this visit, but it never happened, because it was closed. But I took the photo. And I think it took me nearly about 25 years before I actually started learning photography. Now we are talking about 2009, so that’s ten years ago. I was at that point a professor of history dealing with totalitarian systems.

At which university? In Tel Aviv?

At that point I was teaching at the Bezalel Academy of the Arts and Design in Jerusalem. And I was also studying. First year, first grade, first semester with my students. Of course they didn´t know that I was the Head of the history and theory department in Bezalel.

So you were professor and at the same time as well a student?

Yes, first year student. And the other students didn´t know. It took some time before they started asking. And no, I didn´t say anything. You can ask Eli Singalovski as well, he is also participating at this exhibition here. He is a photographer and was also studying with me in 2009 as first year. And so I said: Why do I not go back to Germany and see what happened? All of these buildings I´ve been teaching about, all these architects and photographers, the images of Leni Riefenstahl, Albert Speer, Heinrich Hoffmann, they were rushing through my head over all those years because I am a historian. But I never had a real encounter with those buildings and so I was invited by the Goethe Insitut to do a tour. And I went to Germany in 2009 for about three weeks all the way from Berlin down to Munich and then all the way back. I took hundreds of photos and this was supposed to be a single journey. I gave it the title “The Nazi Phantom” which later became a book. It was published in Israel back in 2014. And it was supposed to be a once in a life time tour. But the things that I saw in Germany were so amazing and so interesting, in terms of solutions and everything. The Interviews that I gave, the people that I met and the ability to discuss the past, the “Erinnerungskultur”, the motivation to deal with history.

There is a difference when you compare it to Japan and their way of dealing with the past like we spoke before.

There should be a very big difference between the first generation, which of course gives testimony to what happened, and the second generation, which is of course traumatized. And then there is the third generation which might be able not only to criticize but to analyze and to learn from history to become different. What I saw in Germany was this amazing in terms of the changes adopted by the society between the first decades after the war and nowadays. And it really made me feel that I must come back again. So from one single journey there was the second and then there was the third and the fourth. And this here now is basically journey number 35 here in Frankfurt. From Germany moved to Italy and from Italy I moved to Poland and from Poland to Russia.

Before you mentioned you just have been to Krakau. So you visited really a lot of places. Do you look especially for places where bad things happened? Like where there was destruction or war, and you go to that places and look what is left and how the surrounding is dealing with it? Is this a correct description?

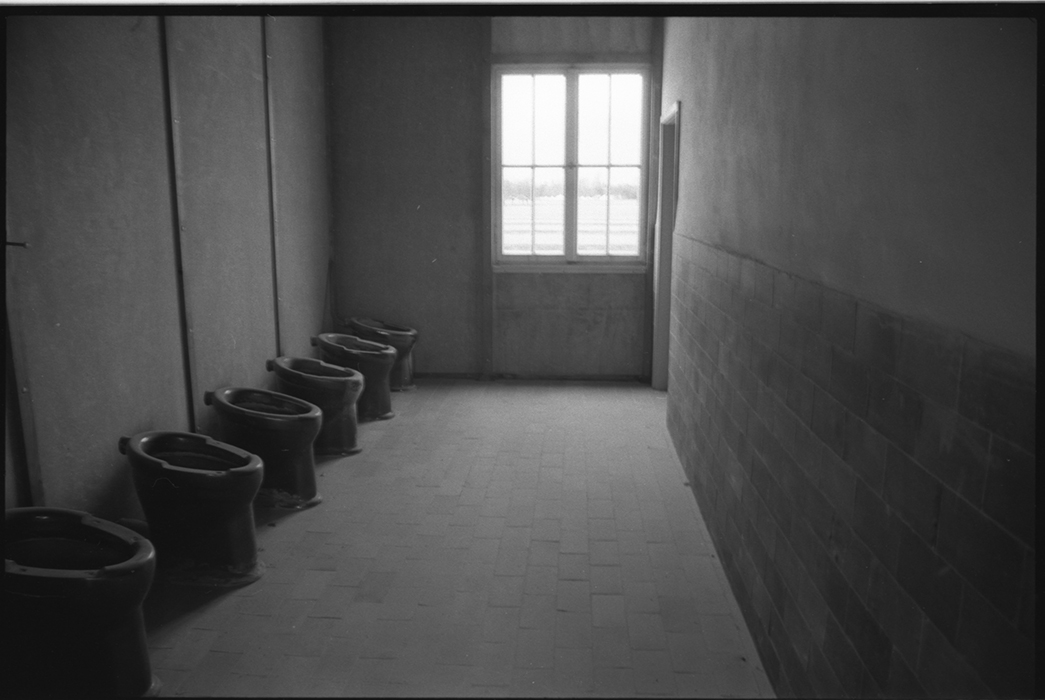

The concept is to go back not to the architecture of the perpetuators as we know it. My concept would not go back necessarily to concentration camps, because these are places people know. I want to shed light on places that normal people do not visit. It could be bunkers, it could be places that are closed to the general public or it could be elementary schools. It could be many places that show you the architecture, the design, the objects, mainly the relics and what is left behind. And what can we learn from the treatment of these relics. If it even exists. I was three month ago in Thessaloniki in Greece. And again there you see a memory culture which is not so open to discussion. Very similar to what we spoke about in Japan. There is a very big difference in pointing a house that still exists after the atomic bombs and to say that this is a house, and the dealing to ask why it was bombed, what are the reasons and what can we learn from it. There is a very big gap and the same thing exists for instance in Thessaloniki. It exists also in Bulgaria and many places around the world. As well in Ukraine or in Russia. They are not necessarily dealing with the results.

It doesn´t has to be an atomic bomb, that is just an absolute extreme at this point. So I understand what you want to show. The people only see how it looks like afterwards, but it´s also about to tell how it looked like before, that it happened because of something and to tell the reasons and whys. So there is much more about it and you want to highlight it a bit more?

I think so and I also think that there is a very big gap between showing an image and asking somebody to interpret what they see. Because my concept is: “Please stay there for a minute!” We are rushing between images very fast. And we look at them briefly. Just a moment to think about it. What´s going on there? Why is it there? It doesn´t matter which concept it is and if you contemplate a little bit you can think about: What is this causing in me? And sometimes it´s really touching. It is very touching because if you hear somebody from Japan telling you his grandmother´s or grandfather´s story because of a picture, so this is something what is really important for me. This is bringing history back to present times. And if I was an art historian and still teaching, like I do of course, but what kind of professor would I be without understanding what was the right way for my students to contemplate and to think. This is a visual culture in which we are living today. So if you manage to stop a person and let him or her think and look at an image and then write something, what more can you ask for.

You gave an impulse to the brain and the heart and even if it´s sometimes just a little touch, that´s perfect. That is what art should do and be.

Exactly. That´s what I am hoping to achieve. So please inform your readers about the website and hopefully some would join in! Enter the page and drop a view words! Either on the German parts or on the Japan and the Far East part section or Poland. It depends and wherever you want. I hope people from all over Europe are listening. And it would be great if people are contributing texts and postings.

So it´s one of the concepts and you want to have the visitors adding posts and writing comments?

Yes. It´s already online for about five years now. When you enter the website you see a very big map of the world. And you click on the country that relates to you. If it´s Italy or Germany or something else. And then of course immediately when you are going into the area or the country, you can see that many of the images there are already darkened with red. These are the images that already have a comment, so on the site there are today over 1000 comments. And the comments can be added to another. So if you write a comment and somebody else wants to write a comment on the same image, it is not a problem. The ones which are red are already taken and have a comment, so that´s the concept, but of course more comments can be added to one image.

THE ARTIST ABOUT HERSELF ON HER WEBSITE

Professor Dana Arieli is a researcher and a photographer. Arieli is an associate professor and her research deals with the interrelations between Art and Politics in both Totalitarian and Democratic political systems. She has completed her Ph.d. at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and studied Photography in Camera Obscura and Bazelel. Between 2012 and 2018 she served as the Dean of Design Faculty at Holon Institute of Technology. Between 2004 and 2012 she served as the head of the History and Theory Department in Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. In recent years Arieli presented some solo photography exhibitions in Israel. Her first Solo Exhibition was accompanied with the catalogue “Closer than they Appear: Givat Ram” (2013). During 2018 and 2019 she was participating in a few solo exhibitions: “That Vary Sea”, was opened in Tel Aviv (2018), ״Boarder Places in Hamburg (2018), “The Nazi Phantom” in the Museum for Persecuted Arts in Solingen (2019) and recently “The Polish Phantom” at the Museum of Contemporary art in Krakow during 2019. She is now working on a new solo exhibition called “The Zionist Phantom” (to be opened during 2021).

Professor Dana Arieli has written numerous articles and books, among the works she published are:

- Phantoms: Journeys After the Relics of Dictatorships (Editor and Photography, 2016)

- The Nazi Phantom: A Journey after the relics of the Third Reich (Author. Resling, 2014. the book includes a Photography-catalog

- Scared Stiff: Terror and its visualisation in art and popular culture (Editor with Dafna Sering, Jerusalem: The Hebrew University Magnes Press, 2011)

- Creators and Dictators: Avantgarde and Mobilised Art in Totalitarian Regimes (Author. Tel Aviv: Tel-Aviv University Press, 2008, Hebrew)

- Creators in Overburden: Rabin Assassination, Art and Politics (Author. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University Magnes Press and Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, 2005, Hebrew, Winner of Prime-Minister award of the state of Israel, 2006

- Romanticism of Steel: Art and Politics in Germany (Author. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University Magnes Press, 1999, Hebrew).

INFOTHEK

![]() Website: https://phantoms.photography/

Website: https://phantoms.photography/

![]() Email: dana63a@gmail.com

Email: dana63a@gmail.com

![]() Facebook: https://web.facebook.com/dana.arieli

Facebook: https://web.facebook.com/dana.arieli

![]() Photo Credits: All images in this article were taken by Dana Arieli during her travels

Photo Credits: All images in this article were taken by Dana Arieli during her travels

MORE ARTICLES ABOUT ISRAEL

>>> Painter Tamir Shefer <<<

>>> Photographer Dana Arieli <<<

>>> Streetart – Tel Aviv <<<

>>> Streetart – Florentin <<<

>>> Streetart – Jerusalem <<<

>>> Interview – Andrew from Capzoola <<<

>>> Interview – Sprayer EVYA <<<